In the volatile world of crypto where a coin can be worth five cents one day and five dollars two months later, the idea of a “stablecoin” — a cryptocurrency whose price experiences relatively little volatility — seems like an oxymoron. Yet more and more stablecoins are appearing these days: just last month, Paxos, Gemini, and Circle all launched their own high-profile stablecoins.

The value proposition of stablecoins isn’t always apparent. In fact, it isn’t even clear that the crypto community has reached a consensus on what it takes for something to be a stablecoin: there are still debates today about whether Bitcoin will ultimately become a “stablecoin” or not. In this article, we’ll consider the possible advantages and disadvantages to stablecoins, and what’s at stake when people discuss whether or not Bitcoin will eventually become “stable.”

What is a Stablecoin?

For most people involved with crypto right now, the term “stablecoin” probably calls to mind cryptocurrencies that are pegged to and backed by a fiat currency. Notice, though, that the definition we used above — a cryptocurrency whose price experiences relatively little volatility — is broader than that. Especially at this early stage in crypto innovation, it seems premature to identify fiat-backed cryptocurrencies as the sole possible implementation of cryptocurrencies with relatively little volatility in price.

To that end, it’s helpful to abstract even beyond crypto and try to better understand currency stability by asking a non-crypto question: Is the U.S. dollar a “stablecoin”?

Remember that the core aspect of stablecoins we’re focusing on is “relatively little volatility.” So, in order to answer this question, we first have to determine what we’re comparing the USD’s volatility to.

One may ask whether the USD is stable relative to the S&P 500, but a moment’s reflection will reveal that this is backwards: because Americans pay in USD, buy goods with USD, and measure their wealth in USD, it wouldn’t make sense to measure the USD’s stability against an American stock market index.

Instead, we might consider the USD’s volatility relative to other fiat currencies, such as the Euro. Of course, that invites the question: at this point, is one looking at volatility of USD or volatility of Euro? It’s really a matter of perspective: you’re determining their volatility relative to each other.

One back-of-the-envelope way to do this would be by comparing the U.S. Dollar Index to the Euro Currency Index, each of which compares its respective currency’s value against a basket of other currencies.

This is a chart of the U.S. Dollar Index over the last ten years, with a chart of its historical volatility underneath it:

And here, for comparison, is a chart of the Euro Currency Index and its volatility during the same period:

This first-glance comparison shows that, while the USD and EUR have both experienced volatility over the years, the USD appears to have been more stable over the past 10 years. Though the two currencies have experienced similar volatility curves, EUR has typically experienced proportionately more volatility throughout the curve, peaking at 43% volatility in May 2009 when the USD peaked at 33% volatility, and bottoming at about 10% volatility in April 2014 when the USD bottomed at 8%.

The lesson here is that “stablecoin” doesn’t mean “zero volatility”: instead, a stablecoin has low volatility, relative to something else. In practice, this means many people in crypto are trying to create a coin whose price follows that of a relatively stable fiat currency — that’s why, as we’ll consider below, some developers are pegging or backing their stablecoins with USD.

It turns out that there are at many different ways in which cryptocurrency developers are trying to make that happen. Below, we’ll highlight four such methods.

A Phylogeny of Stablecoins

The four different ways that developers have found to create stablecoins, each of which comes with distinct costs and benefits.

1. Pegging the Stablecoin

One way to try to make a cryptocurrency (or any currency, for that matter) stable is to peg it to a different, more stable currency or asset. A peg is essentially an enforced, unchanging exchange rate between the stablecoin and the more stable currency or asset. The gold standard is a classic example of a pegged currency, in which the external value of currency was denominated in quantities of gold. A current example in the crypto space is Basis.

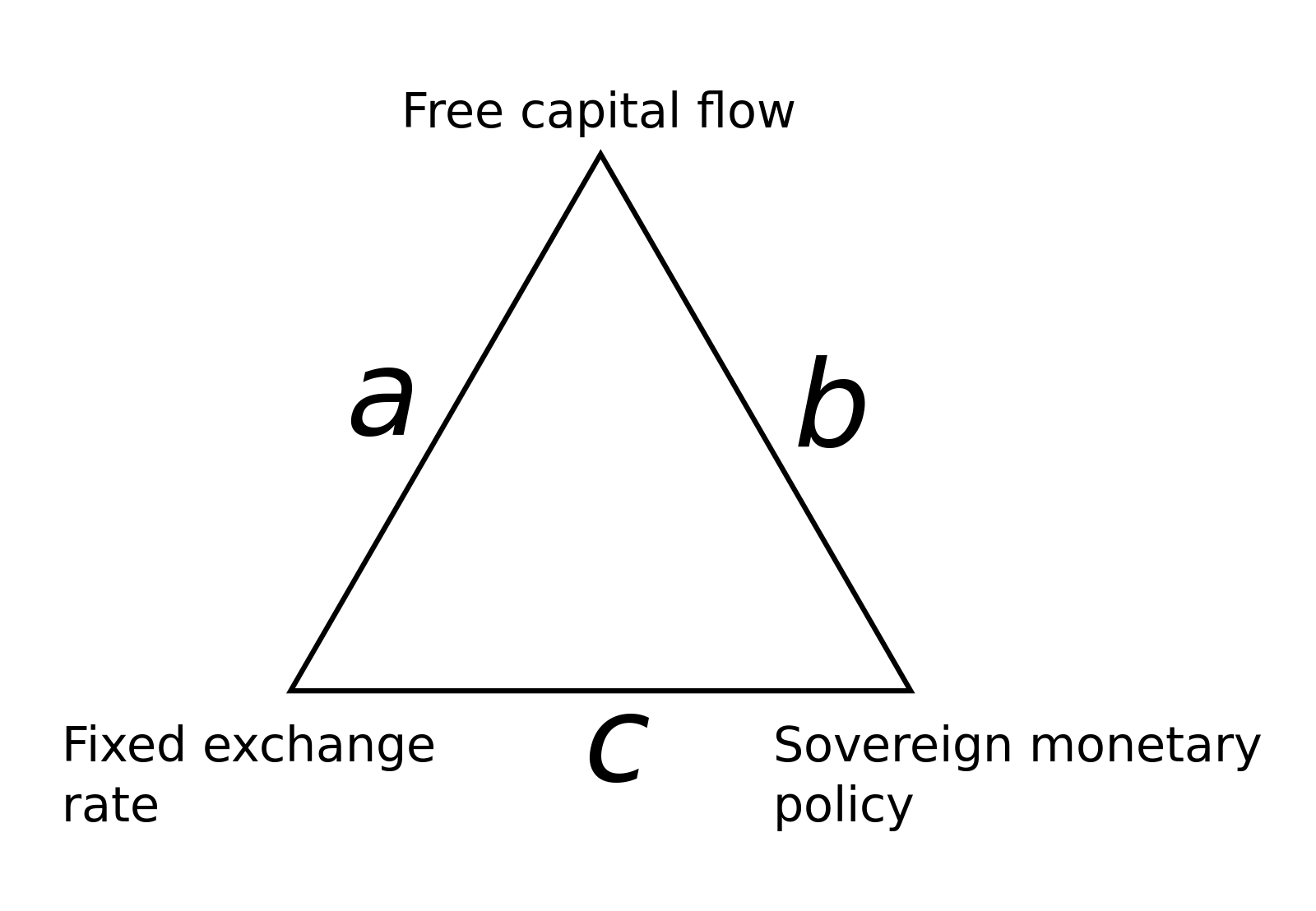

The problem with pegged currencies is that the currency issuers often end up making very deleterious sacrifices for the sake of enforcing the peg. Economic theorists represent this problem in the form of a trilemma called “The Impossible Trinity,” represented by this diagram:

The trilemma is that the issuer of a currency can take Position A, B, or C, but each one requires them to sacrifice one point of the triangle. So, in order to peg a currency, one must sacrifice either free capital flow or sovereign monetary policy — something that has damaged the economies of emerging market currencies that have tried to stabilize themselves through a peg.

When a country tries to peg its currency to another country’s, it could lead that country’s economy to struggle with high inflation and low economic growth if it compromises on monetary policy or free capital flow. One could argue, though, that a cryptocurrency does not necessarily have the same economic considerations that a country has.

If a stablecoin is created solely for transactional purposes, it could be possible for it to sacrifice sovereign monetary policy or free capital flow without completely undermining itself. On the other hand, if the coin is meant to drive a specific blockchain’s ecosystem and provide it with utility, then a peg could end up making it markedly more difficult to use and develop that blockchain.

2. Legacy Currency Controls

Another method of creating a stablecoin is simply by providing a traditional central bank to determine the coin’s inflation rate, supply, and other currency controls. This is the method that’s being tested by some blockchains — most notably, Ripple acts as a kind of “central bank” for its associated cryptocurrency, XRP.

This kind of stablecoin is also being explored by some countries that have seen their citizens turning to cryptocurrencies in order to avoid hyperinflation and other poor economic policies in their native fiat currency. Yet it doesn’t seem that a stablecoin is poised to solve the underlying problems in this case: their respective governments are apt to manipulate them or force their citizens to use them in the same ways that they would a fiat currency.

These stablecoins might conceivably end up being better than the fiat currencies they’re intended to replace, but it’s not clear precisely how they’d do that: they don’t do much at all to move away from a centralized model.

3. Program a Central Bank into the Stablecoin

An experimental alternative to Option #2 above is to build the currency controls of a central bank directly into a token’s economics, rather than relying on an actual central bank. A few crypto projects, such as Basis, are currently developing this model, but it’s too early-stage and experimental to evaluate precisely how this will compare to other methods of establishing a low-volatility cryptocurrency.

4. Back the Stablecoin by Another Currency or Asset

Since this is the most common type of stablecoin today, we’re going to dig deeper into exactly how this kind of stablecoin works, along with its costs and benefits, in the following two sections of the article.

You’d be forgiven if you thought that backing a stablecoin with a currency or asset is the same thing as pegging it to a currency or asset — in popular discourse around stablecoins, the two terms sometimes appear to be used interchangeably. In reality, though, these are two distinct ways of building a stablecoin. Remember that pegging a stablecoin to a currency or asset just involves setting and enforcing a constant exchange rate; when you back your stablecoin with a currency or asset, there is actually a trusted entity that holds a certain amount of that currency or asset for each stablecoin in circulation.

An easy way to conceptualize this is as the crypto version of a cashier’s check.

The Promise of a Digital Cashier’s Check

A stablecoin that’s backed by another currency, like the U.S. dollar of Chinese yuan, is essentially a digital cashier’s check.

A cashier’s check is backed by the funds of a trust third party: a bank. Stablecoins apply this same principle to blockchain-grounded tokens. Unlike most cryptocurrencies (including Bitcoin), this type of stablecoin is backed by physical assets (typically fiat currency, so far) held by a trusted third party. For instance, PAX is backed by the U.S. dollar: each token is meant to always be valued at $1 because each token is really backed by and redeemable for one U.S. dollar, held by a regulated trust, Paxos.

Notice that, when set up in this way, stablecoins cut against the grain of one major element of crypto culture: they tend towards centralization, rather than decentralization. For this reason, stablecoins aren’t poised to radically eliminate the need for all third parties and trust in centralized organizations — something that some view as the core value of cryptocurrency.

That’s not to say that stablecoins are useless. Far from it: this underscores the capacity of blockchain technology to spawn a rich diversity of use cases, not all of which need to be decentralized. The ability to send digital cashier’s checks around the world in real time with low fees has the potential to transform global finance, and that’s the basic value proposition of stablecoins.

When Stablecoins are Less than Stable

There are two major roadblocks to stablecoins realizing their basic value proposition: lack of adoption and lack of trust.

Like many cryptocurrencies, stablecoins won’t be especially useful until they are adopted by the mainstream. But stablecoins face different roadblocks to adoption than cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Litecoin do:

- Some people in the mainstream hesitate when it comes to cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Litecoin because it isn’t clear what they’re backed by. Stablecoins don’t have that problem: they’re pegged to, and backed by, fiat currencies.

- On the other hand, it’s not apparent to many people (1) why they ought to use a token that’s backed by a fiat currency rather than just using the fiat currency itself, and (2) why they ought to choose one stablecoin over another stablecoin (there are currently 15 different stablecoins, according to CryptoSlate).

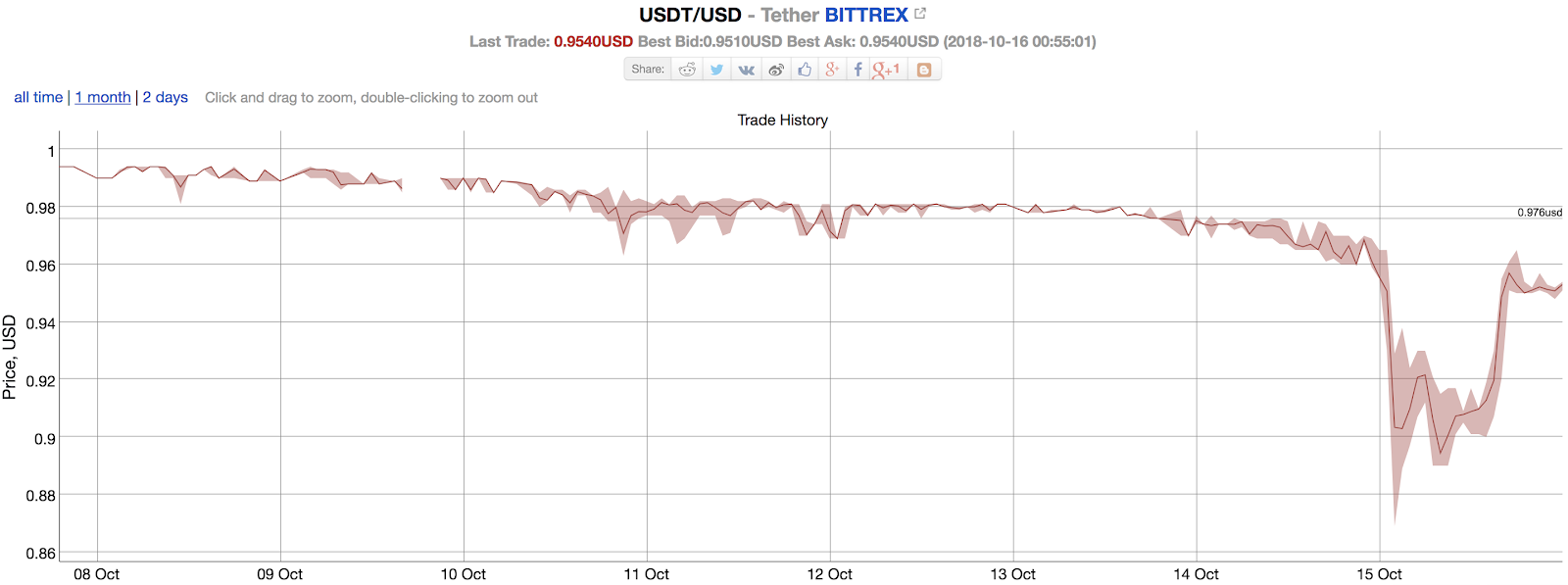

When it comes to determining which stablecoin one should use, trust takes center stage: because stablecoins embrace centralization rather than advocating for decentralization, they need to demonstrate that their respective governing entities are, in fact, trustworthy. We’ve seen as recently as this past Monday what can happen when a stablecoin’s trustworthiness comes into question: as investors and institutions came to doubt whether Tether really had the collateral to back all of its USDT stablecoins. The price of USDT itself — a “stablecoin” issued by Tether using Strategy #4 above, with $1 USD allegedly backing each coin — fell lower than $0.90 USD.

As USDT showed us, a stablecoin losing value can be a vicious cycle that pushes the price lower: if traders and investors who took a position in a stablecoin to avoid crypto volatility see the coin’s price moving, they’re likely to sell their holdings in favor of something more stable, pushing the offending stablecoin’s price lower still.

Stablecoins are aware of the central role trust plays in their service, which is why some are aggressively focusing on transparent regulation and oversight to back up their claims of a fully collateralized, fiat-pegged cryptocurrency. Paxos, for instance, took strides by gaining approval and oversight of its stablecoin, PAX, by a government regulatory body: the NYDFS. At the same time that the market was questioning the legitimacy of USDT on Monday, PAX was announcing that they had been adopted by 20 leading exchanges and OTC desks in their first month of circulation, with over $36 million USD in tokens issued, all of which are backed by dollars in FDIC-insured banks.

Ultimately, stablecoins may find themselves in a similar situation to where some see Bitcoin today: collectively threatening each other because too many different cryptocurrencies are vying to serve the same function, fragmenting a nascent and still relatively fragile ecosystem. Unlike Bitcoin, on the other hand, the stablecoin’s key to success will be proving that it has a robust and trustworthy centralized entity backing it.

Bitcoin’s Choice between Stability and Volatility

But what if Bitcoin could become a stablecoin itself? Even though we’ve spent much of this article treating Bitcoin and stablecoins as fundamentally different, there are some who discuss Bitcoin as if it might eventually be functionally identical to something like PAX.

Before we evaluate that issue, it’s important to clarify what people probably mean when they talk about Bitcoin becoming like a stablecoin. They typically don’t mean that all bitcoins will eventually be collateralized by fiat currency or guided by a central bank: instead, they’re projecting a point in the future at which the price of a bitcoin will be relatively stable, like a stablecoin: subject only to forex volatility, rather than the distinct volatility that currently characterizes the crypto market.

We won’t attempt to forecast whether Bitcoin will or won’t stabilize over time, but we do want to suggest that this question actually represents a broader decision that the Bitcoin community will ultimately have to make together: Is Bitcoin a stable store of value, or an asset with highly fluctuating rates of return?

If Bitcoin is going to serve as a reliable method of storing and transferring value, then — like other stores of value, such as currency or gold — its price needs to be fairly stable. That’s not to say that it can’t appreciate over time (gold, after all, appreciates over time), but regular swings of 100%+ in returns year over year would be counterproductive to this function. By definition, an asset with the extreme volatility we’ve seen thus far in Bitcoin is not a stablecoin.

Ultimately, like everything in Bitcoin, the community will have to find consensus around this issue. So far, they seem to be leaning towards the store-of-value scenario: most people appear to be in favor of a future where widespread Bitcoin adoption leads the price of BTC to become less volatile as the cryptocurrency becomes less of a speculative instrument and more of a currency. If that future comes to pass, Bitcoin could become a stablecoin after all.

Stability in Volatile Markets

Right now, stablecoins mostly have utility for investors and traders who want to close and open crypto positions as efficiently as possible. A compelling stablecoin offers near-instant settlements that are backed by fiat without being an inefficient as fiat.

For stablecoins to be a useful global tool in the long run, though, they’ll need to look beyond the crypto markets to make worldwide transactions faster and cheaper. The leading stablecoins are already laying the foundation for this by building trust, inviting transparency and proactively seeking regulation.

The above references an opinion and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended as and does not constitute investment advice, and is not an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any cryptocurrency, security, product, service or investment. Seek a duly licensed professional for investment advice. The information provided here or in any communication containing a link to this site is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject SFOX, Inc. or its affiliates to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. Neither the information, nor any opinion contained in this site constitutes a solicitation or offer by SFOX, Inc. or its affiliates to buy or sell any cryptocurrencies, securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or provide any investment advice or service.